From Zero hedge – Originally published by Michael Snyder via The Economic Collapse blog,

Get ready for another major worldwide credit crunch. Today, the entire global financial system resembles a colossal spiral of debt. Just about all economic activity involves the flow of credit in some way, and so the only way to have “economic growth” is to introduce even more debt into the system. When the system started to fail back in 2008, global authorities responded by pumping this debt spiral back up and getting it to spin even faster than ever. If you can believe it, the total amount of global debt has risen by $35 trillion since the last crisis. Unfortunately, any system based on debt is going to break down eventually, and there are signs that it is starting to happen once again.

For example, just a few days ago the IMF warned regulators to prepare for a global “liquidity shock“. And on Friday, Chinese authorities announced a ban on certain types of financing for margin trades on over-the-counter stocks, and we learned that preparations are being made behind the scenes in Europe for a Greek debt default and a Greek exit from the eurozone. On top of everything else, we just witnessed the biggest spike in credit application rejections ever recorded in the United States. All of these are signs that credit conditions are tightening, and once a “liquidity squeeze” begins, it can create a lot of fear.

Over the past six months, the Chinese stock market has exploded upward even as the overall Chinese economy has started to slow down. Investors have been using something called “umbrella trusts” to finance a lot of these stock purchases, and these umbrella trusts have given them the ability to have much more leverage than normal brokerage financing would allow. This works great as long as stocks go up. Once they start going down, the losses can be absolutely staggering.

That is why Chinese authorities are stepping in before this bubble gets even worse. Here is more about what has been going on in China from Bloomberg…

China’s trusts boosted their investments in equities by 28 percent to 552 billion yuan ($89.1 billion) in the fourth quarter. The higher leverage allowed by the products exposes individuals to larger losses in the event of stock-market drops, which can be exaggerated as investors scramble to repay debt during a selloff.

In umbrella trusts, private investors take up the junior tranche, while cash from trusts and banks’ wealth-management products form the senior tranches. The latter receive fixed returns while the former take the rest, so private investors are effectively borrowing from trusts and banks.

Margin debt on the Shanghai Stock Exchange climbed to a record 1.16 trillion yuan on Thursday. In a margin trade, investors use their own money for just a portion of their stock purchase, borrowing the rest. The loans are backed by the investors’ equity holdings, meaning that they may be compelled to sell when prices fall to repay their debt.

Overall, China has seen more debt growth than any other major industrialized nation since the last recession. This debt growth has been so dramatic that it has gotten the attention of authorities all over the planet…

Wolfgang Schaeuble, Germany’s finance minister says that “debt levels in the global economy continue to give cause for concern.”

Singling out China in particular, Schaeuble noted that “debt has nearly quadrupled since 2007″, adding that it’s “growth appears to be built on debt, driven by a real estate boom and shadow banks.”

According to McKinsey’s research, total outstanding debt in China increased from $US7.4 trillion in 2007 to $US28.2 trillion in 2014. That figure, expressed as a percentage of GDP, equates to 282% of total output, higher than the likes of other G20 nations such as the US, Canada, Germany, South Korea and Australia.

This credit boom in China has been one of the primary engines for “global growth” in recent years, but now conditions are changing. Eventually, the impact of what is going on in China right now is going to be felt all over the planet.

Over in Europe, the Greek debt crisis is finally coming to a breaking point. For years, authorities have continued to kick the can down the road and have continued to lend Greece even more money.

But now it appears that patience with Greece has run out.

For instance, the head of the IMF says that no delay will be allowed on the repayment of IMF loans that are due next month…

IMF Managing Director Christine Lagarde roiled currency and bond markets on Thursday as reports came out of her opening press conference saying that she had denied any payment delay to Greece on IMF loans falling due next month.

Unless Greece concludes its negotiations for a further round of bailout money from the European Union, however, it is not likely to have the money to repay the IMF.

And we are getting reports that things are happening behind the scenes in Europe to prepare for the inevitable moment when Greece will finally leave the euro and go back to their own currency.

For example, consider what Art Cashin told CNBC on Friday…

First, “there were reports in the media [saying] that the ECB and/or banking authorities suggested to banks to get rid of any sovereign Greek debt they had, which suggests that maybe the next step will be Greece exiting,” Cashin told CNBC.

Also, one of Greece’s largest newspapers is reporting that neighboring countries are forcing subsidiaries of Greek banks that operate inside their borders to reduce their risk to a Greek debt default to zero…

According to a report from Kathimerini, one of Greece’s largest newspapers, central banks in Albania, Bulgaria, Cyprus, Romania, Serbia, Turkey and the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia have all forced the subsidiaries of Greek banks operating in those countries to bring their exposure to Greek risk — including bonds, treasury bills, deposits to Greek banks, and loans — down to zero.

Once Greece leaves the euro, that is going to create a tremendous credit crunch in Europe as fear begins to spread like wildfire. Everyone will be wondering which nation will be “the next Greece”, and investors will want to pull their money out of perceived danger zones before they get hammered.

In the past, other European nations have been willing to bend over backwards to accommodate Greece and avoid this kind of mess, but those days appear to be finished. In fact, the finance minister of France openly admits that the French “are not sympathetic to Greece”…

Greece isn’t winning much sympathy from its debt-wracked European counterparts as the country draws closer to default for failing to make bailout repayments.

“We are not sympathetic to Greece,” French Finance Minister Michael Sapin said in an interview at the International Monetary Fund-World Bank spring meetings here.

“We are demanding because Greece must comply with the European (rules) that apply to all countries,” Sapin said.

Yes, it is possible that another short-term deal could be reached which could kick the can down the road for a few more months.

But either way, things in Europe are going to continue to get worse.

Meanwhile, very disappointing earnings reports in the U.S. are starting to really rattle investors.

For example, we just learned that GE lost 13.6 billion dollars in the first quarter…

One week following the announcement that it would dismantle most of its GE Capital financing operations to instead focus on its industrial roots, General Electric reported a first quarter loss of $13.6 billion.

The results were impacted by charges relating to the conglomerate’s strategic shift. A year ago GE reported a first quarter profit of $3 billion.

That is a lot of money.

How in the world does a company lose 13.6 billion dollars in a single quarter during an “economic recovery”?

Other big firms are reporting disappointing earnings numbers too…

In earnings news, American Express Co. late Thursday said its results were hurt by the strong U.S. dollar, which reduced revenue booked in other countries. Chief Executive Kenneth Chenault reiterated the company’s forecast that 2015 earnings will be flat to modestly down year over year. Shares fell 4.6%.

Advanced Micro Devices Inc. said its first-quarter loss widened as revenue slumped. The company said it was exiting its dense server systems business, effective immediately. Revenue and the loss excluding items missed expectations, pushing shares down 13%.

And just like we saw just before the financial crisis of 2008, Americans are increasingly having difficulty meeting their financial obligations.

For instance, the delinquency rate on student loans has reached a very frightening level…

More borrowers are failing to make payments on their student loans five years after leaving college, painting a grim picture for borrowers, according to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.

Student debt continues to increase, especially for people who took out loans years ago. Those who left school in the Great Recession, which ended in 2009, had particular difficulty with repayment, with many defaulting, becoming seriously delinquent or not being able to reduce their balances, the New York Fed said today.

Only 37 percent of borrowers are current on their loans and are actively paying them down, and 17 percent are in default or in delinquency.

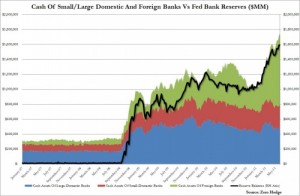

At this point, the American consumer is pretty well tapped out. If you can believe it, 56 percent of all Americans have subprime credit today, and as I mentioned above, we just witnessed the biggest spike in credit application rejections ever recorded.

We have reached a point of debt saturation, and the credit crunch that is going to follow is going to be extremely painful.

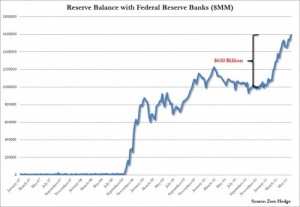

Of course the biggest provider of global liquidity in recent years has been the Federal Reserve. But with the Fed pulling back on QE, this is creating some tremendous challenges all over the globe. The following is an excerpt from a recent article in the Telegraph…

The big worry is what will happen to Russia, Brazil and developing economies in Asia that borrowed most heavily in dollars when the Fed was still flooding the world with cheap liquidity. Emerging markets account to roughly half of the $9 trillion of offshore dollar debt outside US jurisdiction.

The IMF warned that a big chunk of the debt owed by companies is in the non-tradeable sector. These firms lack “natural revenue hedges” that can shield them against a double blow from rising borrowing costs and a further surge in the dollar.

So what is the bottom line to all of this?

The bottom line is that we are starting to see the early phases of a liquidity squeeze.

The flow of credit is going to begin to get tighter, and that means that global economic activity is going to slow down.

This happened during the last financial crisis, and during this next financial crisis the credit crunch is going to be even worse.

This is why it is so important to have an emergency fund. During this type of crisis, you may have to be the source of your own liquidity. At a time when it seems like nobody has any cash, those that do have some will be way ahead of the game.