Via Hugh Hendry’s Eclectica Fund December 2013 Letter to investors,

What if I were to tell you I was turning more bullish? Is that something you might be interested in?

We are macro investors. That means that we are constantly exposed to the shifting sands that the world’s increasingly powerful gaggle of central bankers – and the capital flows they encourage – impose on global financial markets. However we tend to stick to our big (and often bearish) views, something that means our performance comes with hot and cold spells. The most recent one – and it doesn’t take a genius to see this – has been cold. It hasn’t been as bad as it could have been for the simple reason that we make big bets when we are doing well and small bets when we aren’t. We allocate increasing amounts of capital to winning trades and cut losing trades rapidly. We’ve been cutting a lot recently. The good news is that this has minimised our drawdown. The even better news is that our returns have improved lately; it looks as if we are entering a hot spell, and we have begun to re-allocate significantly more risk capital to our endeavours.

So what makes me think we are heading hot at the moment? Let me tell you about the character of Bob Ryan, from the US cable TV show Entourage. The show chronicles the workings of Hollywood and Ryan is a legendary movie producer credited with a string of box office winners. His problem is that his success was rather a long time ago. So no one is certain of his skills anymore. His reaction is to make seemingly absurd promises – think along the lines of “…what if I were to tell you that this movie will cost peanuts to make, will earn you four Oscars and will gross $100m… is that something you might be interested in?” In some walks of life (well, mine anyway) such is the popularity of the show that the expression has entered the modern lexicon as a catchphrase for offering up fantastical, if not actually impossible, ideas. With that in mind, what if I were to tell you that I have adopted a tactically bullish outlook? Is that something you might be interested in?

Last bear standing? Not any more…

I know what you are thinking. You are thinking that the last bear is capitulating. It isn’t a good sign. Maybe it is that simple. But I think it is a little more complicated. We, and I accept we aren’t the first here, sense that US monetary officials may now be willing to subordinate the demands of their own economy to the perils confronting emerging market economies. If that is the case, the great peril is not that the Fed finally tightens monetary policy and US stock prices suddenly tumble from what are very obviously overpriced levels. Would that it were – our curmudgeonly portfolio structure (think dynamic volatility targeting and stop losses) works well with big stock market reversals. Instead the greater peril is that the current backdrop will turn out to mark a rapid acceleration in the ongoing move to the upside. A hint that this might be the case comes from looking back through the 113 years of price data for the Dow Jones Industrial Average. We have done this (so you don’t have to), searching along the way for the comparable periods that fit most tightly to the last 500 trading days. What is clear is that periods of trading similar to the one we have seen over the last two years don’t often seem to end quietly: they boom big time or they crash. Which is it to be this time? Looking at the markets of 1928, 1982 or even 1998, all of which have scarily similar looking historical charts to today’s, we wonder if it won’t be both. Starting with the boom bit.

Let’s look at what happened in 1998. All sorts of market moving events were shifting the sands. There was the fall out from the Asian Tiger crisis. There was Russia’s local currency default. And there were the event risks of the collapse of LTCM and the Y2K scare. Together these things ensured that US monetary policy was set far too loose for the US economy itself. And the result? A parabolic trend to the upside in equities that destroyed anyone who chose to stand in its way. This is what I fear most today: being bearish and so continuing to not make any money even as the monetary authorities shower us with the ill thought-out generosity of their stance and markets melt up. Our resistance of Fed generosity has been pretty costly for all of us so far. To keep resisting could end up being unforgivably costly.

Made a mistake once? Why not make it again…

You will wonder what makes the Fed so concerned that it is willing to risk another bubble and another crash?

The answer rests in the dominance of neo-mercantilism as the most successful economic orthodoxy of our time. For those new to this, the text book definition will suffice. Neo-mercantilism is a policy regime borrowed from 19th century Kaiser Germany. It encourages exports, discourages imports, controls capital movement, and centralises currency decisions in the hands of a central government (to reduce reliance on flighty foreign capital). The point is to increase the level of foreign reserves held by the sovereign government, allowing for an accommodating domestic monetary policy. It also looks like it works — you can make a good case for it being responsible for the superior growth rates seen across Asia since the 1980s. However it comes with what I think is about to be a major problem. It has made domestic monetary policy in most Asian countries very pro-cyclical and we haven’t really yet tested this pro-cyclicality to the downside. What happens when the rest of the world becomes unwilling to raise its indebtedness further in order to buy Asian-produced products and facilitate Asian growth? And what if that is about where we are right now?

To date, the experiment with economic growth in Asia has succeeded as an almost direct result of the re-leveraging of the American economy since interest rates began to fall in the early 1980s.

The Japanese authorities blazed a trail on this for everyone to follow. It kicked off with (yet) another credit cycle gone wrong. In the 1970s there was a bubble in lending to Latin American governments. That was popped by Paul Volker’s tightening of US monetary policy. Latin American currencies tumbled and sound currencies soared. Except the yen. Japan had a central plan for economic self-sufficiency – one that required a positive current account and endless rounds of domestically funded investment. They did not want a strong currency, low cost imported goods and a consumer boom or anything else that might have risked future trade deficits. So they worked to keep the yen from appreciating too fast, too soon. How? The Bank of Japan created yen and bought Treasuries. This money found its way into the local banking system (as new money does) where it was soon turbo-boosted by foreign capital inflows: overseas investors were attracted by the corporate profits produced from the loose policy and pretty pleased with the way in which a persistently undervalued exchange rate made asset prices cheap to foreign investors. Chuck in fractional reserve banking, and risk-seeking bankers and it was inevitable that asset prices would surge. The rest is history. Equity prices, ignoring all qualitative objections to bubble valuations, quadrupled. Then they crashed.

First Japan. Now China.

To understand today’s story we have to leave Japan (reluctantly — we’ll come back to it), and travel 20 years later to China, where the same pattern has been repeating itself. Back in 2004. China’s cheap land, cheap labour, cheap money, cheap everything, produced high returns on capital and trade surpluses with the rest of the world which encouraged investment inflows into the country. That, as Charles Kindleberger, the intellectual godfather of macro investing and author of the unsurpassed classic Manias, Panics & Crashes, noted, is the kind of combination that “almost always” leads to an increase in the country’s currency and domestic asset prices.

However Kindleberger was writing pre-neo-mercantilism. He would have expected the follow-on from this to be higher consumption as a result of the wealth effect of higher asset prices (people who feel rich spend more) and of the boost to spending from a rising currency giving falling import prices. He’d have looked at 2004 China and expected every member of the middle class to be driving a cheap BMW by 2006. That didn’t happen. Instead currency interventions held down the yuan and, at the same time, the planners’ need for cheap credit to finance their investment projects meant the real returns from bank deposits were forced to stay firmly negative (if you are going to invest in worse than useless investment projects it mitigates matters somewhat if you insist on the debt being cheap…). Negative deposit rates might make residents of countries with developed welfare states more likely to spend. They appear to make the Chinese more likely to save. You will hear much about the rise of a consumer boom in China in no end of bullish papers. But the truth is different. It is that China is unique in the extent to which it has prevented ordinary people being exposed to cheap BMWs; despite the massive growth in the economy consumption has persistently fallen as a share of GDP. The Kaiser would have approved.

Mercantilism needs a donor. That donor has heen you.

The key point about Japanese and now Chinese mercantilism is that the creation of domestic growth in this way has always required a donor country — the one hosting the consumption boom needed to finance the investment spending back home. In the latest round, cash is injected into Treasuries by China (this is what Bernanke referred to as the “glut of savings”). It is then captured by the US banking system (someone has to sell the Treasuries to the Chinese and manage the proceeds). Then the loop repeats. Chuck in (again!) the fractional reserve banking and your usual bullish community of loan officers in the US and you soon see a rise in economic activity and of course in leverage. Then stock and property prices boom. But it doesn’t end there. Oh no. The boom boosts wealth in the US. They borrow more and spend more — bringing what should be tomorrow’s consumption forward into today. That in turn boosts demand for imports and shovels more dollars into China, something that forces it to print more yuan to keep its currency down and to buy more Treasuries. This cash enters the banking sector… and so on.

All this needs more and more Chinese productive capacity (more steel plants, more concrete, more factories, more ships, more roads, more property, more, more, MORE) to meet the additional foreign demand. China is the host. The US is the donor. The host effectively offers vendor financing to help the donor consume. In return the host gets high domestic investment rates and full employment — both things that help when you are after social obedience and international influence (it’s easy to have a strong foreign policy when your would-be enemy owes you money). And everyone gets rising asset prices. Which is nice. In theory this is an expansion without limit. That sounds like a joke. It’s more an observation.

Limitless prosperity or limitless instability?

This has been our world for some time now. That’s a problem for the likes of us. Why? Because when the psychology of the price discovery mechanism becomes more dependent on money creation than economic growth, as in Japan during the 1980s and in China for the last decade, asset prices become an abstraction. They separate from our qualitative perception of reality; they are more susceptible to wild price trends that in theory have no limit; and they display a two-way causality.

This isn’t how it is supposed to work. In a more normal world you can think of finding value in terms of the one-way causality of a thermometer and room temperature. If we doubt the veracity of the thermometer we can always produce an independent, second, thermometer to determine the proper temperature. The temperature is what it is. Just as in investing, the fundamentals are what they are. But what if it wasn’t like that? What if by warming the mercury in the thermometer, we could also raise the room temperature? This is what happens in the wacky world of neo-mercantilism. Here “fundamental” investing has little or no merit. There is one reason for being long and one alone: sovereign nations are printing money and you can see that prices are trending. That’s it. Nothing else matters. Think of a neo-mercantilist market as if it were a mouse with the toxoplasma virus. The virus hijacks its immune system and makes it fearless. It dies in the end. But not before it does some pretty nutty stuff. There’s no more point in yelling “watch out for the cat” at a mouse hijacked by toxoplasma than there is looking at valuation measures in a market hijacked by mercantilism.

Me and my immune system

My investing immune system has been in pretty good shape recently. But that’s the main reason why I’ve produced mediocre investment performance. I’ve been sensible. But in doing so I have imposed qualitative, one-way causality arguments onto a market that just doesn’t care. I need to be more like the mouse (just without the bit where it dies) and that means I have had to put aside qualitative analysis and be in this trending market. I had thought it would be worth staying bearish and accepting underperformance for the fun of being right in the end – becoming what the British call a vexatious litigant, someone who fights for the sake of it. But I’m not sure any of us can wait that long. Playing it safe, as my good friend Chris Cole wrote last year may be the greatest risk of all.” So the mouse it is.

America fights back

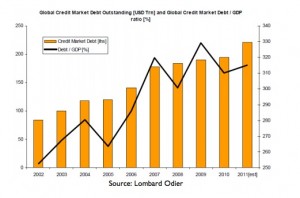

Back to our story. What happens when the donor can’t take it any more? This happened in part in March 2009 when the US rejected Asia’s neo-mercantilism. Two destructive, domestic boom/bust cycles within a decade had left gross debt almost four times GDP. The domestic economy had become unresponsive to even record fiscal expansion and almost zero overnight rates. Something had to be done to regain the initiative. Polite requests for the Chinese to allow their currency to revalue higher versus the dollar were rebuffed and in its absence expansionary American fiscal and monetary policy only served to make China richer. Not ok. So America fought back. With QE.

If the Chinese were never going to revalue their currency themselves, the US would effectively do it for them. QE would target higher prices in China, something that would revalue the renmimbi in real terms and, with a bit of luck, produce the consumer boom that its bureaucrats had so steadfastly sought to prevent. This would transform China into the donor country and also generate the prosperity America needed to recover from the clutches of its debt deflation. And so the sands shifted again. The Fed kicked off its Treasury purchase program in 2009 in the full knowledge that the lack of demand for productive investment in the moribund US economy would create a surplus of speculative flows into faster growing regions of the world. It also knew that such flows would force the foreign exchange targeting emerging market central banks to print even more of their own currencies to keep a lid on their exchange rate appreciation as the dollar debased itself. The Fed then recognised how the chain reaction we have chronicled above would go. Emerging market asset prices would be bid up, something that would in turn be met by more central bank printing of local currencies which would then be leveraged through the emerging market banking system into even higher local asset prices and so on and so on and so on.

The Fed starts winning

This works. Well it works for the Fed. We estimate that total emerging market debt now surpasses $66trn. That’s almost two and a half times emerging market GDP and double its level at the start of the Fed’s QE extravaganza. At the same time car sales in China have surpassed those of the US and property prices are on a rip. Housing transactions are up 35% year on year and new home prices are rising across the nation by between 15% and 20%. Looks like a consumer boom doesn’t it? So from the Fed’s point of view this is going well. So well that since July 2008, the renminbi has appreciated by some 30% against the euro. But while the Fed might be pleased the Chinese probably aren’t.

“When the monster stops growing. it dies. It can’t stay one size.”

The Grapes of Wrath, John Steinbeck

The mercantilist plan has always been to push overseas trade expansion via the perpetuation of an under-valued currency. It isn’t working out. Look at Europe. Europe’s nominal GDP was supposed to be much higher by now (partly on the back of China’s helpful 2009 bout of credit expansion). But it has only surpassed its previous highs by 2%. And denominated in renminbi, it’s much much worse: the European economy has nose-dived by 25% since March 2008. Try being a small labour intensive manufacturer in some coastal Chinese city renowned for its export prowess but struggling with fast rising wages selling into that!

The German philosopher and experimental psychologist scientist, Gustav Fechner, once proposed a rule that can be expressed as follows “in order that the intensity of a sensation may increase in arithmetical progression, the stimulus must increase in geometrical progression?” That seems to describe China pretty well. The huge disappointments in growth elsewhere mean that for China’s GDP to make arithmetic progression, a geometric intensity of effort – with no theoretical end – is required. The monster has to grow. Note that since the Fed turned the tables with its QE policy in 2009, China has had to consume more concrete in its roads, rail projects, bridges, factory construction and new buildings than the US did during the entire 20th century. Yet despite this Herculean effort its structural growth rate has fallen by 30%. This is all fascinating. But tell you what it isn’t. It isn’t stable. It is what China expert Michael Pettis would call a volatility machine.

Markets predicting deflation get asset inflation

Something happened in April of this year that I think may have marked a turning point. Before I go into that I want to be sure we all understand something. You want to believe that China’s growth rate over the last 30 years has been a triumph of superior state planning and the irrepressible force of urban migration, a one way causality if you like. I’d like to too. But we have to accept that it just isn’t true. Instead it is the result of a system of foreign exchange suppression – and so anchoring our expectations to it is a very bad idea. With that in mind, I’m going to ask you to consider the US Treasury Inflation Protected Securities (TIPS) market. As you know, we allocate a lot of time and risk capital to equities. Their malleability allied with low transaction costs and liquidity make them an excellent way for us to invest in our macro narratives. But we find it hard to buy and sell equities based on valuations. Doing it like this is just too imprecise. So we prefer the certainty of inflation expectations: you should be long equities if inflation expectations are trending higher — or more specifically for us when the 10-year inflation expectation, derived from the TIPS market, is greater than its 200 day moving average.

Over the last decade you could have done this and nothing else and escaped most criticism. A simple trading rule where one is long S&P futures when the condition is met, and flat otherwise, has produced a return of 75% since the 1st of January 2003 (around the bottom of the TMT crash). A long-only strategy has produced better gains – almost 95% – but using the rule would have lowered your maximum drawdown from 56% to just 20%. So once you adjust for volatility you can say that you would have done better investing guided by trend inflation expectations than not. The 10-year expectation moved below its 200 day moving average in April this year. And yet we have taken a resolutely contrarian message from this signal. Don’t sell equities. China’s pledge to maintain high GDP growth rates by ploughing on with capacity enhancing supply additions to its fixed capital formation, even at a time when the still risk averse banking system in Europe and America is failing to produce a consumer boom in the West, is fast building global deflationary pressure. That’s the resounding message from the TIPS market. And in a world of two way causality, that could continue to prove immensely bullish. Why? Because the Fed uses this criteria as its principal benchmark for determining whether to taper or not.

So imagine the virtuous loop that runs through asset prices today. The Fed begins QE to thwart neo¬mercantilism and capture more of its own domestic expansion. The Chinese witness a shortfall in their GDP growth rates as their overseas expansion moderates. This robs them of the ability to loosen policy in the West. They counter by embarking on more fixed capital formation to maintain a floor on domestic GDP growth. This adds to the global supply equation that drives break-even inflation expectations lower and leads the Fed to once more embark on yet looser monetary conditions. It is a reflexive cycle that can drive mice to be madder and madder. Or braver and braver. Depends how you look at it. But either way, only a foolish investor would stand in the way of this bull market. It’ll crash of course, just not for a while.

Want to make real money? Make it in Japan

What if I were to tell you that you could buy something for $300k and it might be worth $5m in a couple of years? Is that something you might be interested in?

Japan has never been very far away from my thoughts. I’ve grown old as its economy and stock market have languished from the aftershocks of their equity price bubble in the 1980s. My first year as an investment analyst in Edinburgh was spent conducting research on Japanese stocks in the year immediately after the bubble had popped. I remember the denial on the part of my superiors that the show had ended. It’s hard to accept you have luck not talent.

Later I remember being struck by how the Dow Jones Industrial Average had broken its 1929 price high 25 years later in 1954. That really captured my imagination. I don’t know why. Perhaps even then it was the notion of an economic life cycle savings hypothesis. That people make consumption decisions based on their current stage of life. That we have roughly 23 years or so to accumulate savings and a pension to see us through our less industrious later years. It made sense to me that regardless of the stock market bubble in the 1920s, 25 years should be sufficient to take out a nominal price established so long ago. I reasoned that even low rates of inflation compound to quite a large number over so many years. And that the nature of social democracies is that they dislike prolonged hardship. If things get so bad then sooner or later they are going to vote for politicians who will address their concerns.

So I started looking around to see whether I could find other asset classes that complied with this pattern. Gold caught my attention. The price high of January 1980 struck me as being similar in magnitude to what took place on Wall Street all those years previously. Gold flew from its shackles of $35 an ounce in 1970 to sell briefly for more than $800 in January 1980; and then it crashed. But the nominal price high was taken out 27 years later on the 28th December 2007. The silver market had been cornered at the peak making its price high that much more difficult to surmount. It needed 31 years to re-establish the old price high. The oil market took just 24 years to break the $40 handle last seen in March 1980. Interesting isn’t it?

I then became fascinated by the 7th of December 1941. Yes it was the date of the attack on Pearl Harbour but it also represented an incredibly rare occurrence: the Dow Jones traded at its 50-year price moving average. John Templeton bought his “penny” stocks and the rest was history. This brings me to Japan. The TOPIX stock price index has recently traded as low as its 50-year moving average and better still, next December will mark the 25th anniversary of its great price peak.

Maybe this doesn’t mean anything. But it is our contention that Japan’s long spell in the sin bin has left its society particularly vulnerable to the charms of a radicalisation of monetary policy. We reckon that with the pro-growth shocks of neo-mercantilism essentially having run their course, Japan will struggle to produce the incremental GDP necessary to service and repay its gigantic sovereign debt load. This will provoke inflationary price targeting by a politicised central bank that should send Japanese stock prices heavenwards once more. I’m not eulogising about Abenomics and its golden arrows here. Instead I’m expressing a more negative kind of bullishness: the fear of persistent policy failure that leads to fiat money printing without limit.

Back in 2008, with world equity markets in turmoil, I purchased a one-touch 40k Nikkei call option for which we paid $300k. I could envisage the yen strengthening substantially and triggering a corporate shock as Japanese household names buckled under the duress of currency appreciation. I also bought a lot of credit protection. And sure enough, in 2011 and for the majority of 2012 the yen strengthened. Japan recorded its largest manufacturing bankruptcy and a number of prominent household names, the giant electronic businesses, saw the cost of insuring their debt sky-rocket. For instance, Sharp rose from a spread of around 100 in January 2012 to over 5,900 in October of the same year. The Japan iTraxx Index for five-year protection, however, only flared to 220 (from around 100 in 2010) and so our hypothesis that much of corporate Japan would buckle under the weight of yen strength proved unfounded.

That was a shame but nevertheless, this “crisis-lite” was sufficient to produce the political intervention that we had envisaged. The most senior policy makers at the Bank of Japan were unceremoniously removed from office and monetary policy was set, instead, very loosely, propelling yen asset prices higher. The stock market leapt by 60% on the news and the currency weakened by 20%. And, as the chart below of the Japanese five-year break-even inflation expectation reveals, one should be long their stock market. We still value the one-touch at our purchase price today, and with the market approaching 16k and trending higher, who is to say where it will trade in April 2018? If it touches 40k, get $5m.

CHART PAGE 7

Where will it all end?

Remarkably, the aftershocks of Japan’s volte-face seemed to catch American policy makers out. In May, the Fed, convinced that its QE program had succeeded in re-distributing global GDP away from China and towards the US economy, began signalling its intent to taper its easy money by autumn. However, with 10-year Treasury rates having moved from 1.75% to 3% and its fourth largest trading partner having devalued by 20% since the previous November, the anticipated vigorous domestic American growth never actually materialised; it was captured instead by the new and even looser monetary policy of Japan. Yet again the reflexive loop had worked to sustain the monetary momentum that is feeding global stock markets. And the not so all-knowing Fed? It had to shock market expectations in October by removing the immediacy of its tighter policy and stock markets rebounded higher. Where will this all end? Can it ever end?

There are multiple possible outcomes. The one markets are most vulnerable to is the re-emergence of bullish bankers. They could lend such that the consumer boom in the US and Europe finally sparks and in doing so provoke the Fed to finally tighten policy. That would spook developed market equities but not as much as you might think – they will have the palliative of the stronger GDP growth. Emerging market equities are closer to the edge of a bubble and could prove more susceptible to a greater drawdown owing to the fragilities of their debt fuelled economies. But for now, the re-emergence of risk-seeking bankers fuelling a lending boom in the West seems remote. We aren’t too worried about it. In Europe for instance the banking system has an estimated 2.6trn euros of deleveraging (circa 30% of GDP) still to complete, having shed 3.5trn euros already.

So we are happy to run a long developed market stock position with a short hedge composed of emerging market equity futures. We are running an unhedged long in Japanese equities as our wild bullish card (we have, of course, hedged the currency).

It seems then to us that the most likely outcome is that America and Europe remain resilient without booming. But with monetary policy set so much too loose it is inevitable that we will continue to witness mini-economic cycles that convince investors that economies are escaping stall speed and that policy rates are likely to rise. This will scare markets – and emerging markets in particular – but it won’t actually materialise: stronger growth in one part of the world on the back of easier policy will be countered by even looser policy elsewhere (the much fabled “currency wars”). So market expectations of tighter policy will always be rescinded and emerging markets will recover rather than crash. Developed markets just keep trending positively against this background – and might accelerate. Remember what we said about 1928 and 1998 at the beginning.

Just be long. Pretty much anything.

So here’s how I understand things now that I am no longer the last bear standing. You should buy equities if you believe many European banks and their sovereign paymasters are insolvent. You should buy shares if you put a higher probability than your peers on the odds of a European democracy rejecting the euro over the course of the next few years. You should be long risk assets if you believe China will have lowered its growth rate from 7% to nearer 5% over the course of the next two years. You should be long US equities if you are worried about the failure of Washington to address its fiscal deficits. And you should buy Japanese assets if you fear that Abenomics will fail to restore the fortunes of Japan (which it probably won’t). Hey this is easy…

And then it crashed

I have not completely lost my senses of course. Eclectica remain strong believers in the most powerful force in the universe – compounding positive returns – and avoiding large losses is crucial to achieving this.

We have built a reputation for getting the calls right in the difficult space that is macro investing, which has served us and our clients well during both trending bull markets and times of crisis. Today, of course, the market is “golden” which is to say that the 50 day price trend is above the 200 day. But remember that during those forays into the “dead-zone”, years like 2008 and 2011 when equity markets crashed, Eclectica performed handsomely. I like to think therefore that I own an alpha crisis management franchise that has rewarded our investors at limes of stock market stress.

This commitment remains as resolute as at any time over the last 11 years that I have managed the Fund. But what if I could produce a consistent alpha return profile with the in-built crisis hedge to your wealth… is that something you might be interested in?