Next Downleg

From Porter Stansberry in the S&A Digest

Porter Stansberry: The next stage of the crisis is starting now

Monday, June 20, 2011We’re about to see a return to crisis-like conditions in the world’s credit markets. This will devastate financial stocks. It should also hit commodity prices and commodity-related stocks hard. In today’s Digest, I’ll show you why I believe this will happen.

As longtime readers know, I write Friday’s Digest personally. In general, I try my best to teach our subscribers something useful. I’ve always run my research company with a few simple principles in mind. Among them, I strive to provide you with the information I would expect if our roles were reversed. You should know… abiding by this principle often requires me to share information with you before I can be 100% certain it’s correct.

That’s the case with today’s Digest. I want to show you the warning signs as I see them, right now. I want to guide you through my thinking process. And while I’ll give you my predictions about what these things mean, I hope you’ll realize that, as Yogi Berra famously said, predictions are tough – especially about the future.

The next stage in the ongoing global financial crisis will feature the collapse of both the Spanish and the Italian economies. This should occur within the next six months. Concurrently, I believe the “Chinese miracle” will be unmasked as mostly a fraud powered by a huge increase in bad lending from state-controlled banks.

Ironically, the coming wave of financial trouble will probably force people back into U.S. dollars. Gold will also do well. In the currency markets, I believe the euro will collapse in the second half of this year, as will the Australian dollar, which serves as a proxy for the Chinese economy.

I expect this next “down leg” in the world’s markets to be more severe than the crisis of 2008, because the balance sheets of the Western democracies are now less prepared to manage the losses.

Finally, I believe the euro will simply cease to exist.

The first thing I want to show you is the share price of UniCredit. You have probably never heard of UniCredit, but it is a major European bank, with significant operations in eastern and southern Europe. UniCredit is based in Italy. I’ve been keeping my eye on UniCredit for years, for reasons I’ll explain below. UniCredit is the ultimate “canary in the coal mine” of the world’s global currency system.

Most people don’t know that UniCredit is the direct descendent of Oesterreichische Credit-Anstalt, the largest bank in Eastern Europe before World War II. Translated the name means: Imperial Royal Privileged Austrian Credit-Institute for Commerce and Industry. It was a Rothschild bank. The family founded it 1855, and it became one of the most important banks in Europe.

Credit-Anstalt held assets and took deposits from all over Europe. In 1931, the bank failed as a direct result of the U.S.’s Smoot-Hawley tariff. The act crippled Germany’s economy and led French investors to redeem all the capital they’d lent to the bank. The failure of Credit-Anstalt caused Austria to abandon the gold standard, which set off a series of economic dominoes. Germany left gold… then Great Britain… and finally, in 1933, so did America.

The failure of Credit-Anstalt is what really kicked off the Great Depression. I have long been convinced the failure of its successor bank – now called UniCredit – would presage the next global monetary collapse.

I first began warning investors about UniCredit’s likely collapse and its historic role in the world’s monetary history back in March 2010. Since then, the bank’s shares have grown weaker and weaker. And since March, the shares have fallen off a cliff, hitting lows not seen since March 2009.

The sudden weakness in UniCredit’s shares (down 21% in the last several weeks) indicates to me that big trouble is brewing in Europe. I don’t believe efforts to stop the crisis in Greece will work. The austerity measures undertaken in Ireland, Spain, Italy, and Greece have severely weakened these economies, causing loan losses to banks like UniCredit.

And if there’s a run on UniCredit (and I believe there will be), the losses will be too large for Italy to manage without a huge international bailout. UniCredit has borrowed $300 billion from other European banks. And Italy’s government already owes creditors more than 120% of GDP. There aren’t any easy solutions to this problem.

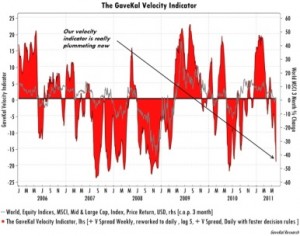

Another warning comes from a friend who is a senior executive at a major Wall Street bank. He sees more high-yield bond deals than just about anyone else in the world. He told our Atlas 400 group last weekend that credit markets around the world were suddenly shutting down. Yields were moving up. Spreads (the cost to borrow above the sovereign rate) were getting wider for the first time since March 2009.

Why? Because the market knows that the U.S. Federal Reserve is going to stop buying $85 billion-plus per month of U.S. Treasury debt. But the Treasury is going to continue to issue more debt. In total, 61% of the entire federal debt will mature within four years. That means roughly $10 trillion in U.S. Treasury bonds will have to be sold, plus whatever the total deficit adds up to over the next four years – maybe another $6 trillion.

It’s difficult to imagine this amount of Treasury issuance won’t have a big impact on the world’s credit markets because these bonds always sell first and at the lowest yields. As these yields “back up” because of the large issuance, they should drain liquidity away from other issues, causing other bond prices to fall. This will reduce liquidity and make issuing debt more expensive across the credit spectrum.

China’s boom since 2009 was fueled by massive domestic debt issuance, which was unsustainable and is reversing. In addition, one Chinese company after another is being revealed as a fraud – and then crashing. These are not isolated events. I have studied Chinese companies for more than a decade. Out of all the stocks I’ve analyzed closely, I’ve only seen a handful I didn’t believe were fraudulent.

So far, none of the major Chinese banks have come under serious scrutiny. But I believe they will… and I believe major fraud will be discovered. Take the recent weakness in the shares of China Life Insurance (LFC), for example. This isn’t a minor company. It’s a $90 billion life insurance company. As fraud allegations spread into major Chinese financials, the entire underpinning of the Chinese boom will fall apart. It has all been fueled by debt and fixed-asset investments (land, buildings, equipment, and machinery). Consider just a few of these facts…

Fixed-asset investment remains greater than 50% of GDP in China, for the 12th year in a row. No other country has ever had more than nine years of this kind of sustained fixed-asset investment.

In the first five months of 2011, fixed-asset investment grew by 25.8% according to China’s National Bureau of Statistics. That’s $1.39 trillion worth of investment.

Jim Chanos, the famed short seller, says China is currently building 30 billion square feet of commercial real estate. That is enough to provide every person in China with a five-square-foot cubicle.

Jeremy Grantham, one of the world’s most astute investors, points out that China has been purchasing gigantic quantities of raw materials. The scale of these purchases makes them impossible to sustain. China makes up 9.4% of the world’s economy, but it is currently consuming 53% of the world’s cement, 47% of the world’s iron ore, and 46.9% of its coal.

A massive increase in China’s domestic debt fueled this investment. In 2010, for example, Chinese banks extended $55 billion in loans – up 95% from the year before. Now, banking regulators are increasing reserve requirements, greatly reducing the amount of available credit. In May, lending was down 25% versus last year.

With Europe’s crisis heating back up, with credit tightening in the U.S. (thanks to the end of quantitative easing), and with China’s boom unraveling… it’s time to be extremely cautious. I don’t know when it will start… but we’re entering another period of soaring volatility, increasing interest rate spreads, and falling stock and bond prices. How the authorities deal with these problems will set the stage for what happens next. If they try to paper over these continuing crises again – with new money-printing programs from the Federal Reserve – you can expect a massive inflation and what I call The End of America.

Our best hope for more stability and a return to prosperity is for people to realize that bailing out banks doesn’t solve these problems. It only makes them worse. But… I’m not optimistic. In the June issue of my newsletter, Stansberry’s Investment Advisory, I detail my best two new ideas to profit from the next stage of this crisis.

Comment » | Deflation, EUR, Geo Politics, PIIGS, The Euro, USD