This is a great article which I am reposting from John Mauldin’s Outside the Box E-Letter.

You should sign up here

Three Competing Theories

By Lacy Hunt, Hoisington Asset Management

The three competing theories for economic contractions are: 1) the Keynesian, 2) the Friedmanite, and 3) the Fisherian. The Keynesian view is that normal economic contractions are caused by an insufficiency of aggregate demand (or total spending). This problem is to be solved by deficit spending. The Friedmanite view, one shared by our current Federal Reserve Chairman, is that protracted economic slumps are also caused by an insufficiency of aggregate demand, but are preventable or ameliorated by increasing the money stock. Both economic theories are consistent with the widely-held view that the economy experiences three to seven years of growth, followed by one to two years of decline. The slumps are worrisome, but not too daunting since two years lapse fairly quickly and then the economy is off to the races again. This normal business cycle framework has been the standard since World War II until now.

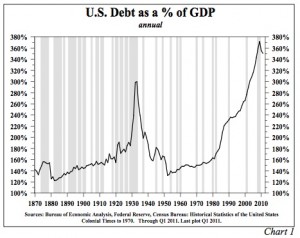

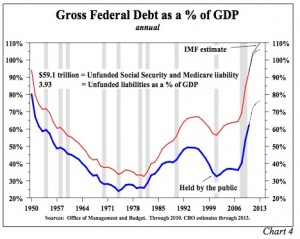

The Fisherian theory is that an excessive buildup of debt relative to GDP is the key factor in causing major contractions, as opposed to the typical business cycle slumps (Chart 1). Only a time consuming and difficult process of deleveraging corrects this economic circumstance. Symptoms of the excessive indebtedness are: weakness in aggregate demand; slow money growth; falling velocity; sustained underperformance of the labor markets; low levels of confidence; and possibly even a decline in the birth rate and household formation. In other words, the normal business cycle models of the Keynesian and Friedmanite theories are overwhelmed in such extreme, overindebted situations.

Economists are aware of Fisher’s views, but until the onset of the present economic circumstances they have been largely ignored, even though Friedman called Irving Fisher “America’s greatest economist.” Part of that oversight results from the fact that Fisher’s position was not spelled out in one complete work. The bulk of his ideas are reflected in an article and book written in 1933, but he made important revisions in a series of letters later written to FDR, which currently reside in the Presidential Library at Hyde Park. In 1933, Fisher held out some hope that fiscal policy might be helpful in dealing with excessive debt, but within several years he had completely rejected the Keynesian view. By 1940, Fisher had firmly stated to FDR in several letters that government spending of borrowed funds was counterproductive to stimulating economic growth. Significantly, by 2011, Fisher’s seven decade-old ideas have been supported by thorough, comprehensive and robust econometric and empirical analysis. It is now evident that the actions of monetary and fiscal authorities since 2008 have made economic conditions worse, just as Fisher suggested. In other words, we are painfully re-learning a lesson that a truly great economist gave us a road map to avoid.

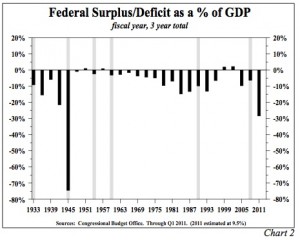

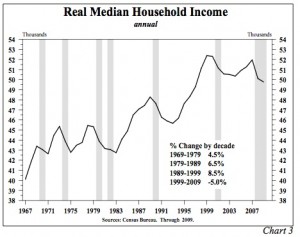

High Dollar Policy Failures

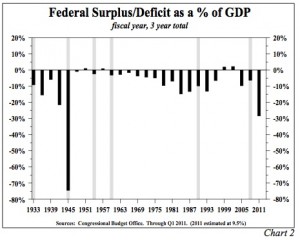

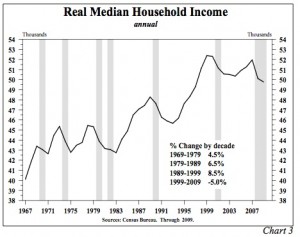

If governmental financial transactions, advocated by following Keynesian and Friedmanite policies, were the keys to prosperity, the U.S. should be in an unparalleled boom. For instance, on the monetary side, since 2007 excess reserves of depository institutions have increased from $1.8 billion to more than $1.5 trillion, an amazing gain of more than 83,000%. The fiscal response is equally unparalleled. Combining 2009, 2010, and 2011 the U.S. budget deficit will total 28.3% of GDP, the highest three year total since World War II, and up from 6.3% of GDP in the three years ending 2008 (Chart 2). Importantly, the massive advance in the deficit was primarily due to a surge in outlays that was more than double the fall in revenues. In the current three years, spending was an astounding $2.2 trillion more than in the three years ending 2008. The fiscal and monetary actions combined have had no meaningful impact on improving the standard of living of the average American family (Chart 3).

Why Has Fiscal Policy Failed?

Four considerations, all drawn from contemporary economic analysis, explain the underlying cause of the fiscal policy failures and clearly show that continuing to repeat such programs will generate even more unsatisfactory results.

First, the government expenditure multiplier is zero, and quite possibly slightly negative. Depending on the initial conditions, deficit spending can increase economic activity, but only for a mere three to five quarters. Within twelve quarters these early gains are fully reversed. Thus, if the economy starts with $15 trillion in GDP and deficit spending is increased, then it will end with $15 trillion of GDP within three years. Reflecting the deficit spending, the government sector takes over a larger share of economic activity, reducing the private sector share while saddling the same-sized economy with a higher level of indebtedness. However, the resources to cover the interest expense associated with the rise in debt must be generated from a diminished private sector.

The problem is not the size or the timing of the actions, but the inherent flaws in the approach. Indeed, rigorous, independently produced statistical studies by Robert Barro of Harvard University in the United States and Roberto Perotti of Universita Bocconi in Italy were uncannily accurate in suggesting the path of failure that these programs would take. From 1955 to 2006, Dr. Barro estimates the expenditure multiplier at -0.1 (p. 206 Macroeconomics: A Modern Approach, Southwestern 2009). Perotti, a MIT Ph.D., found a low but positive multiplier in the U.S., U.K., Japan, Germany, Australia and Canada. Worsening the problem, most of those who took college economic courses assume that propositions learned decades ago are still valid. Unfortunately, new tests and the availability of more and longer streams of macroeconomic statistics have rendered many of the well-schooled propositions of the past five decades invalid.Second, temporary tax cuts enlarge budget deficits but they do not change behavior, providing no meaningful boost to economic activity. Transitory tax cuts have been enacted under Presidents Ford, Carter, Bush (41), Bush (43), and Obama. No meaningful difference in the outcome was observable, regardless of whether transitory tax cuts were in the form of rebate checks, earned income tax credits, or short-term changes in tax rates like the one year reduction in FICA taxes or the two year extension of the 2001/2003 tax cuts, both of which are currently in effect. Long run studies of consumer spending habits (the consumption function in academic circles), as well as detailed examinations of these separate episodes indicate that such efforts are a waste of borrowed funds. This is because while consumers will respond strongly to permanent or sustained increases in income, the response to transitory gains is insignificant. The cut in FICA taxes appears to have been a futile effort since there was no acceleration in economic growth, and the unfunded liabilities in the Social Security system are now even greater. Cutting payroll taxes for a year, as former Treasury Secretary Larry Summers advocates, would be no more successful, while further adding to the unfunded Social Security liability.

Third, when private sector tax rates are changed permanently behavior is altered, and according to the best evidence available, the response of the private sector is quite large. For permanent tax changes, the tax multiplier is between minus 2 and minus 3. If higher taxes are used to redress the deficit because of the seemingly rational need to have“shared sacrifice,” growth will be impaired even further. Thus, attempting to reduce the budget deficit by hiking marginal tax rates will be counterproductive since economic activity will deteriorate and revenues will be lost.

Fourth, existing programs suggest that more of the federal budget will go for basic income maintenance and interest expense; therefore the government expenditure multiplier may become more negative. Positive multiplier expenditures such as military hardware, space exploration and infrastructure programs will all become a smaller part of future budgets. Even the multiplier of such meritorious programs may be much less than anticipated since the expended funds for such programs have to come from somewhere, and it is never possible to identify precisely what private sector program will be sacrificed so that more funds would be available for federal spending. Clearly, some programs like the first-time home buyers program and cash for clunkers had highly negative side effects. Both programs only further exacerbated the problems in the auto and housing markets.

Permanent Fiscal Solutions Versus Quick Fixes

While the fiscal steps have been debilitating, new programs could improve business considerably over time. A federal tax code with rates of 15%, 20%, and 25% for both the household and corporate sectors, but without deductions, would serve several worthwhile purposes. Such measures would be revenue neutral, but at the same time they would lower the marginal tax rates permanently which, over time, would provide a considerable boost for economic growth. Moreover, the private sector would save $400-$500 billion of tax preparation expenses that could then be channeled to other uses. Admittedly, the path to such changes would entail a long and difficult political debate.

In the 2011 IMF working paper, “An Analysis of U.S. Fiscal and Generational Imbalances,” authored by Nicoletta Batini, Giovanni Callegari, and Julia Guerreiro, the options to correct the problem are identified thoroughly. These authors enumerate the ways to close the gaps under different scenarios in what they call “Menu of Pain.” Rather than lacking the knowledge to improve the economic situation, there may not be the political will to deal with the problems because of their enormity and the huge numbers of Americans who would be required to share in the sacrifices. If this assessment is correct, the U.S. government will not act until a major emergency arises.

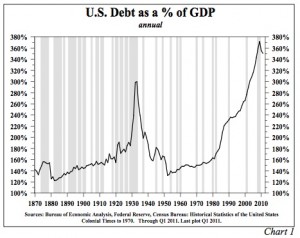

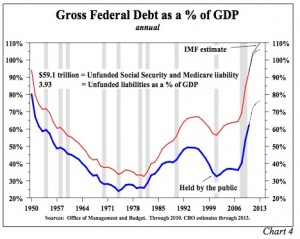

The Debt Bomb

The two major U.S. government debt to GDP statistics commonly referred to in budget discussions are shown in Chart 4. The first is the ratio of U.S. debt held by the public to GDP, which excludes federal debt held in various government entities such as Social Security and the Federal Reserve banks. The second is the ratio of gross U.S. debt to GDP. Historically, the debt held by the public ratio was the more useful, but now the gross debt ratio is more relevant. By 2015, according to the CBO, debt held by the public will jump to more than 75% of GDP, while gross debt will exceed 104% of GDP. The CBO figures may be too optimistic. The IMF estimates that gross debt will amount to 110% of GDP by 2015, and others have even higher numbers. The gross debt ratio, however, does not capture the magnitude of the approaching problem.

According to a recent report in USA Today, the unfunded liabilities in the Social Security and Medicare programs now total $59.1 trillion. This amounts to almost four times current GDP. Modern accrual accounting requires corporations to record expenses at the time the liability is incurred, even when payment will be made later. But this is not the case for the federal government. By modern private sector accounting standards, gross federal debt is already 500% of GDP.

Federal Debt – the End Game

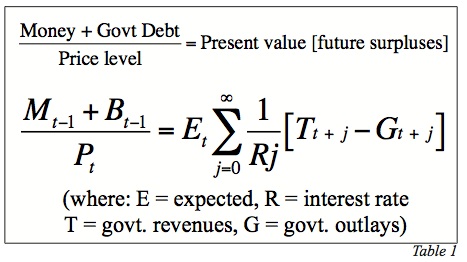

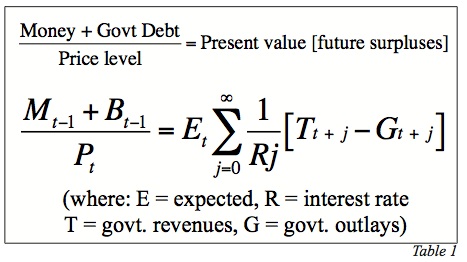

Economic research on U.S. Treasury credit worthiness is of significant interest to Hoisington Management because it is possible that if nothing is politically accomplished in reducing our long-term debt liabilities, a large risk premium could be established in Treasury securities. It is not possible to predict whether this will occur in five years, twenty years, or longer. However, John H. Cochrane of the University of Chicago, and currently President of the American Finance Association, spells out the end game if the deficits and debt are not contained. Dr. Cochrane observes that real, or inflation adjusted Federal government debt, plus the liabilities of the Federal Reserve (which are just another form of federal debt) must be equal to the present value of future government surpluses (Table 1). In plain language, you owe a certain amount of money so your income in the future should equal that figure on a present value basis. Federal Reserve liabilities are also known as high powered money (the sum of deposits at the Federal Reserve banks plus currency in circulation). This proposition is critical because it means that when the Fed buys government securities it has merely substituted one type of federal debt for another. In quantitative easing (QE), the Fed purchases Treasury securities with an average maturity of about four years and replaces it with federal obligations with zero maturity. Federal Reserve deposits and currency are due on demand, and as economists say, they are zero maturity money. Thus, QE shortens the maturity of the federal debt but, as Dr. Cochrane points out, the operation has merely substituted one type for another. The sum of the two different types of liabilities must equal the present value of future governmental surpluses since both the Treasury and Fed are components of the federal government.

Calculating the present value of the stream of future surpluses requires federal outlays and expenditures and the discount rate at which the dollar value of that stream is expressed in today’s real dollars. The formula where all future liabilities must equal future surpluses must always hold. At the point that investors lose confidence in the dollar stream of future surpluses, the interest rate, or discount rate on that stream, will soar in order to keep the present value equation in balance. The surge in the discount rate is likely to result in a severe crisis like those that occurred in the past and that currently exist in Europe. In such a crisis the U.S. will be forced to make extremely difficult decisions in a very short period of time, possibly without much input from the political will of American citizens. Dr. Cochrane does not believe this point is at hand, and observes that Japan has avoided this day of reckoning for two decades. The U.S. may also be able to avoid this, but not if the deficits and debt problem are not corrected. Our interpretation of Dr. Cochrane’s analysis is that, although the U.S. has time, not to urgently redress these imbalances is irresponsible and begs for an eventual crisis.

Monetary Policy’s Numerous Misadventures

Fed policy has aggravated, rather than ameliorated our basic problems because it has encouraged an unwise and debilitating buildup of debt, while also pursuing short term policies that have increased inflation, weakened economic growth, and decreased the standard of living. No objective evidence exists that QE has improved economic conditions. Even before the Japanese earthquake and weather related problems arose this spring, real economic growth was worse than prior to QE2. Some measures of nominal activity improved, but these gains were more than eroded by the higher commodity inflation. Clearly, the median standard of living has deteriorated.

When the Fed diverts attention with QE, it is possible to lose sight of the important deficit spending, tax and regulatory barriers that are restraining the economy’s ability to grow. Raising expectations that Fed actions can make things better is a disservice since these hopes are bound to be dashed. There is ample evidence that such a treadmill serves to make consumers even more cynical and depressed. To quote Dr. Cochrane, “Mostly, it is dangerous for the Fed to claim immense power, and for us to trust that power when it is basically helpless. If Bernanke had admitted to Congress, ‘There’s nothing the Fed can do. You’d better clean this mess up fast,’ he might have a much more salutary effect.” Instead, Bernanke wrote newspaper editorials, gave speeches, and appeared on national television taking credit for improved economic conditions. In all instances these claims about the Fed’s power were greatly exaggerated.

Summary and Outlook

In the broadest sense, monetary and fiscal policies have failed because government financial transactions are not the key to prosperity. Instead, the economic well-being of a country is determined by the creativity, inventiveness and hard work of its households and individuals.

A meaningful risk exists that the economy could turn down prior to the general election in 2012, even though this would be highly unusual for presidential election years. The econometric studies that indicate the government expenditure multiplier is zero are evidenced by the prevailing, dismal business conditions. In essence, the massive federal budget deficits have not produced economic gain, but have left the country with a massively inflated level of debt and the prospect of higher interest expense for decades to come. This will be the case even if interest rates remain extremely low for the foreseeable future. The flow of state and local tax revenues will be unreliable in an environment of weak labor markets that will produce little opportunity for full time employment. Thus, state and local governments will continue to constrain the pace of economic expansion. Unemployment will remain unacceptably high and further increases should not be ruled out. The weak labor markets could in turn force home prices lower, another problematic development in current circumstances. Inflationary forces should turn tranquil, thereby contributing to an elongated period of low bond yields. The Fed may resort to another round of quantitative easing, or some other untested gimmick with a new name. Such undertakings will be no more successful than previous efforts that increased over-indebtedness or raised transitory inflation, which in turn weakened the economy by directly, or indirectly, intensifying financial pressures on households of modest and moderate means.

While the massive budget deficits and the buildup of federal debt, if not addressed, may someday result in a substantial increase in interest rates, that day is not at hand. The U.S. economy is too fragile to sustain higher interest rates except for interim, transitory periods that have been recurring in recent years. As it stands, deflation is our largest concern, therefore we remain fully committed to the long end of the Treasury bond market.