From Paul Brodsky and Lee Quaintance of QBAMCO

Another Perspective (pdf)

Two weeks ago, before Jamie Dimon’s thoughtful diversion, Charlie Munger of Berkshire Hathaway instructed viewers of CNBC that “civilized people don’t buy gold, they invest in productive businesses”. Munger was right in that civilized people invest in productive businesses and was right to imply that gold is a non-productive rock, but, in our humble opinion, he was wrong to suggest that gold does not have significant upside as an investment currently (even more than BRK/A?).

Gold has always been money, as are dollars, euros and yen. It is not a currency or media of exchange presently because no one directly exchanges it for goods, services or assets and it has not formally collateralized other currencies since 1971. However, were gold to once again back today’s baseless currencies, then it would be astonishingly cheap at today’s exchange rates with them (i.e. gold prices), and by extension cheap to most operating businesses denominated in today’s currencies. Gold today is a speculation that someday it will again have recognized monetary status.

Gold is a store of purchasing power bought at certain exchange rates to other currencies – as we write this, about $1,600 an ounce to the dollar, €1,232 an ounce to the Euro, £988 an ounce to sterling, and ¥127,790 an ounce to yen. In the current monetary system in which all global currencies are uncollateralized, the perception of gold’s exchange rate (price) ultimately derives from its status as potential monetary collateral that might someday back government-sanctioned (fiat) money.

Thus, when gold is money or formally backs currencies, people save gold. Given its un-sanctioned monetary status today, gold may be considered an investment. Given its intrinsic cheapness vis-à-vis paper currencies today and economic conditions that make it highly likely it will become even cheaper to them, very civilized people across the world have been replacing a portion of their fiat cash and financial asset portfolios with gold not held in their investment portfolios. (The only way to hold physical bullion in a financial asset portfolio would be to own shares in mining companies, which provide direct ownership of physical bullion inventories held below ground.)

Despite the incessant negative chatter about gold by people in positions of influence, (or more likely because of it), there has been only a trifling allocation to it among financial asset investors. The vast majority of dedicated financial asset and derivative investors, including pension funds, mutual funds, individuals, and even futures speculators, remain either; a) unable to invest in it by charter, b) unconvinced that gold’s price will appreciate over a time horizon that matches their mandates, c) convinced that gold is a poor investment at today’s pricing because authorities will let bank system credit fail, or d) oblivious to what gold is and the economic forces behind it.

Precious metals allocations account for only about 0.15% of global pension fund assets. Within the gold futures market, only 0.50% of front month contracts typically take delivery of bullion, implying gold futures remain a source of financial return among speculators, not a means of amassing a physical position. Meanwhile, all gold and silver ETFs combined held only 90 million gold-equivalent ounces as of the end of April, which at about $1,650 an ounce equaled only about $150 billion. (Compare that to Apple’s market cap.) And perhaps the most telling indicator of indifference to gold among financial asset investors: the total market capitalization of all publicly traded precious metal miners (representing trillions in below-ground physical reserves) is only about $360 billion.

We think there are four main questions to be asked and answered: 1) how does one handicap what would be a multi-sigma event – whether or not gold will again gain formal monetary status; 2) over what time horizon might the perception of a significant change in the global monetary system occur (and would it include gold); 3) what would be a range of investment outcomes should such an event occur; and 4) how would such pro forma returns compare with the range of returns of other investments? We have devoted much of our research since 2007 to these questions and have written extensively about them. This paper, however, will only seek to place gold in proper perspective for Mr. Munger (and perhaps Mr. Dimon too).

What’s it all About, Charlie?

The difference between saving and investing is that savers seek to maintain their purchasing power and investors seek to increase theirs. In the current environment it is impossible to save at a positive real rate of return given that interest rates are near zero and central banks are diluting purchasing power through monetary inflation. Everyone is forced to speculate – even cash and (especially) bondholders.

Currently, cash, bank deposits and bond holdings denominated in baseless currencies are being diluted by global central banks and losing significant purchasing power, which means “savers” in these instruments are actually speculating this established trend will stop. Their real (inflation-adjusted) returns are already negative (against CPI), and so, by implication, they believe the return of the majority (but not all) of their purchasing power is better than “speculating” in productive businesses to try to generate a positive return on their current purchasing power.

In this, we agree with Charlie Munger’s partner, Warren Buffett; productive assets are better than cash and bonds denominated in baseless currencies. We agree with any implication that saving in fiat cash or fiat-denominated fixed-income instruments is a loser’s game at current pricing. But we would disagree with any implication that it is not the right time to exchange baseless currencies or most productive businesses denominated in them for gold.

A Bit of Theory

Consider that price is the quantity of money assigned to a good, service or asset, yet changing prices may not necessarily have anything to do with the changing value of goods, services and assets. For example, the value to society of a good, service or asset in relation to its quantity can remain constant or even fall; yet its price can rise substantially if the quantity of money increases more than the increase in demand relative to supply. The more monetary units available to chase the same supply/demand equilibrium, the higher the general price level for goods, services and assets must be.

This means that expectations of increasing or decreasing demand in an economy can only partially rationalize future price changes. The more moving parts (e.g. immigration, innovation, government spending, the whims of independent money issuers, etc.) that affect the supply and demand for goods, services, assets, AND MONEY; the less visibility there will be for prices — even if expected value is reasonably knowable. So, in the current monetary system, currencies are indeterminate claims on wealth and purchasing power kept in currency is an imperfect marker of wealth. (Of course, we know currency, per se, is not wealth because if it were then wealth could be created simply by creating more currency.)

An easy way to envision how to quantify purchasing power is to imagine two buckets: the first contains all of the world’s money and the second contains all things not-money. We may debate about the proper relative value of the various items in the money bucket (e.g. dollars, euros, yen, gold, etc.), and debate even more vociferously (and do) about the proper relative values of the items in the all-things-not-money bucket (e.g. toothpaste, labor, accounting fees, stocks, bonds, commodities, iPods, etc); however, it would be illogical to think that the aggregate value of the money bucket should not equal the aggregate value of the all-things-not-money bucket at all times. Conceptually, all the stuff in the world that can be purchased must have a means to be purchased, and so the aggregate value of each bucket must always equal the aggregate value of the other.

So then: if wealth is current and future sustainable purchasing power, and judging the future value of goods, services and assets relies on also judging the quantity of money, and the quantity of money and all the stuff it can buy must always be at equilibrium, then one of the first-order economic considerations among all members of society should be to judge the money in which he or she a) is compensated in, and b) chooses to invest or save in.

Practicalities

Very few people today think about the sustainable value of their money, including, it seems, Messrs. Munger and Buffett. If stocks are cheap to baseless cash, as they rightly argue, and stocks are cheap to gold, as they seemingly imply, then nothing has been determined (or even implied) regarding the relative value of gold to fiat cash within the money bucket. Somewhat strangely, their argument reduces to the contention that money in whatever form it may take – dollars or gold — has no economic function of value. They argue one should hold stocks as a residual claim on productive assets instead. We would vehemently disagree. We see the value in productive businesses; however, one must also consider the possibility that, even if they are intrinsically undervalued in fiat cash terms, productive business may be intrinsically overvalued in gold terms. (Judging by subsequent performance, it certainly seems BRK/A shares were quite overvalued vis-à-vis gold in 2000.)

When objectively defined and properly priced by the marketplace, the presence of money as a savings vehicle enhances the well-being of society. When subjectively rendered and manipulated by goal-oriented policy objectives, the value of money becomes distorted vis-à-vis goods, services, assets and labor. The difference today between investing in baseless currency-denominated productive businesses and exchanging baseless currencies for gold defines the difference between solving for nominal vs. real returns. Investors in most financial assets denominated in over-leveraged currencies today will receive nominal relative returns while gold holders store absolute real purchasing power (save in real terms).

Which is the better bet? The global gold stock increases about 1%-2% a year as compared to the global fiat money stock which increases many multiples of that. This should be the fundamental consideration when it comes to choosing a money form in which to speculate or in which to price one’s investments: which will have its purchasing power diluted less? If Berkshire Hathaway shares rise 25% in the coming years but the US dollars these shares are denominated in fall 35% versus consumer goods and services, then Munger and Buffet will have invested in productive businesses that made profits yet they would have lost purchasing power in the aggregate for shareholders. This dynamic illustrates precisely what has occurred since 2000.

(Safe) Harborous Relic

What exactly are the economics of shiny rocks as they relate to our very civilized contemporary society? The working figure for the amount of all the above-ground gold ever mined is about 170,000 metric tons, which converts to almost 5.5 billion troy ounces (5,465,619,000). At $1,600 an ounce this implies the recognized total value of all the mined gold in the world is a bit over $8.7 trillion today ($8,744,990,400).

Should we believe the 170,000 metric ton figure? Well, annual worldwide production of gold is about 50 million troy ounces. If we were to assume 50 million ounces mined over the last 200 years, (perhaps generous but this assumption would also be sufficient to include ancient mining since the time of the Aztecs), then there would be about 10 billion ounces mined since antiquity. Unlike other metals with industrial uses, gold is not consumed. Every ounce ever mined still exists. At $1,600 an ounce, the total amount of above-ground gold would equal about $16 trillion. So let’s say gold is currently valued somewhere between $8 trillion and $16 trillion.

Governments and their designated central bank currency issuers do not own most of the above-ground gold in the world. The World Gold Council reports that total official gold holdings throughout the world totals almost 31 thousand metric tons (30,878.2 tonnes), which, at today’s pricing, equals about $1.6 trillion ($1,588,357,750,464). Depending on how much gold has actually been mined, 5.5 or 10 billion ounces, the world’s treasury ministries and central banks only have somewhere between 10% and 18% of it.

This presents a problem for governments that would like to control the perceived value of money. There are no currencies today (since 1971) formally linked to gold or any other relatively finite collateral. This implies that virtually all global governments prefer to have direct control over their budgets, rather than allowing the collective will of their societies determine the scale of government spending. Authoritarian and representative governments alike prefer a global monetary system in which money is effectively issued by fiat and directed by appointed monetary policy makers (usually central banks).

The great challenge for elected and appointed monetary policy makers is to try to manage the quantity and pricing of their fiat currencies consistent with the multi-faceted and unpredictable dynamics of the global economy. Fiat currencies must be widely perceived to be priced more or less equitably, not only by the factors of production and wealth holders within each society but also by the various global governments overseeing economies with greatly different resources, social values and natural economic growth rates.

If global money, formally comprised today of all various baseless fiat currencies, were to begin to be perceived in the commercial marketplace as an insufficient marker of the future value for goods, services and assets, (domestically or internationally); then the global monetary system would be in jeopardy. In short, confidence is lost if and when currency is no longer perceived as a sufficient store of value. In such a scenario currency holders would discard it for goods, services and assets at an accelerating pace. Importantly, they would not necessarily exchange their baseless currency for labor or production, which would be an economic stimulant (or for shares of BRK/A). Prices would rise as economic factors of production, private wealth holders, and participating governments further accelerate their consumption of goods or assets they feel would store value better. Baseless currencies would ultimately lose credibility and the the global monetary system would fail.

When systems fail it does not mean that the values of goods, services and assets change, only that the numeraire of money is reset. (The numeraire is the value reference used to base a unit of account.) Global monetary systems periodically need resetting, most frequently in 1933, 1945 and 1971. Changing the numeraire requires the support of global economic agents, including the private marketplace and international government authorities. This, in turn, requires widespread confidence that the value and nature of the re-setting would not lead to an imminent need for further re-settings. This is precisely why gold remains relevant today.

The more “sophisticated” unreserved credit and its uses become, the more unknowable future purchasing power becomes. The more remote baseless currencies that comprise our global monetary system stray from being sustainable stores of value, the likelier it becomes they will be called into question. (Enter JP Morgan’s public recognition that it has an unwieldy balance sheet.)

Perhaps this is why governments and central banks have continued to own gold? You may recall not too long ago Ben Bernanke was asked if he considered gold to be money and he said “no”. When asked why the Fed still owned it, he shrugged and murmured something about “tradition”. You may also recall that more recently he was asked if the Fed owned gold, and he seemed to do his best to appear perplexed. He looked back and forth over his shoulder until finally an aide confirmed that indeed the Fed does hold gold certificates (which give the Fed rights to Treasury’s bullion).

It shouldn’t be shocking that the manufacturer of the world’s reserve currency expresses public bewilderment with the fascination over anachronistic, inert rocks by a few gentlemen with southern accents. What else could he say: pay no attention to gold’s long history of resetting societies’ wealth valuation mechanism against failed currencies? Or pay no attention to other central banks buying gold hand over fist currently? (Perhaps they are doing so because they want to be more traditional?)

All the Right People, Darling

The absolute amount of gold held in official hands – 10%, 18% or even 25% — is meaningless. The important concept to keep in mind is that the stock of official gold holdings throughout all economies is quite small relative to privately held bullion. Somewhere in the world there is between $7 and $15 trillion of gold wealth (at current spot pricing) held in private hands (vs. $1.6 trillion in official accounts). Private wealth holders across the world have been saving gold bullion for generations; in Europe, the Middle East, China, India, Japan, Russia, South America and the United States (even in private pockets on Wall Street, believe it not, where there’s an old saying: “make it on Wall Street, bury it on Main Street”).

It should not be surprising that global central banks have begun buying gold bullion in ever increasing amounts. It was just reported this month that Hong Kong shipped almost 63 metric tons of gold to China in March, a 59% increase over February and a 587% increase year over year. Russia has been a consistent buyer of about 5,000 tonnes each month and has recently accelerated its purchases. Other high growth economies including India cannot seem to get sufficient supplies of bullion. Clearly the governments of these countries want to exchange their baseless and diluting reserves for a scarcer money form. And just this week the IMF – yes, the same IMF that had been selling its bullion to central banks of emerging economies with surplus reserves – announced it was buying $2 billion of gold. The reason: “there is a need to increase the Fund’s reserves in order to help mitigate…elevated credit risks”.

Meanwhile, central banks of developed debtor economies are being pressured by their contracting debt-based economies to manufacture more fiat currencies through the process of debt monetization – issuing even more debt and paying for it with newly-created base money (currency and/or bank reserves held at central banks). They are devaluing their currencies for savers and investors and destroying the future purchasing power of surplus reserves held abroad.

If past is prologue, the baseless currencies of developed economies will eventually be subjected to asset monetization. Greece could solve its debt problems tomorrow if it sold Mykonos for $400 billion and the US could halve its Treasury debt if it sold Alaska for $8 trillion. However, such asset sales seem far more unlikely (and in Alaska’s case, impossible – who could buy it?) than simply revaluing an asset already held in official hands — the asset monetary issuers have always used; the only monetary asset on their balance sheets that can be re-valued higher against the currency they manufacture; (one might say the “traditional” one): gold.

We argue the final outcome must be to devalue current baseless currencies against gold and that governments of high-growth economies are buying official gold in increasing amounts so they have a representative share when gold becomes the basis for a new global monetary system.

Have global private gold savers/investors that comprise the great majority of its holders been buying in advance of a more formal currency reset (devaluation) of baseless paper against gold? Who are central banks buying their physical gold from currently? (Certainly they are not buying it from global commodities exchanges.) The only answer is that they must be buying all they can from the 80% to 90% of private gold holders in the world. And we should ask ourselves this: who has been buying gold consistently since 2000, when it traded around $250 an ounce, 11 years before central banks became net buyers? Could the buyers have been private holders around the world that understand wealth doesn’t begin and end with leveraged Western financial assets and baseless fiat currencies? This would make sense.

Still, the volume of physical gold traded relative to its stock remains tiny, implying that relatively few physical holders are willing to part with most of their gold. If central banks want to stock their shelves prior to devaluation then they would have to employ a bit of finesse. If we were a sovereign in search of gold we would short gold futures and take physical bullion off the market at synthetically low prices (the same way other sovereigns might manipulate, say, interest rates).

And finally, who are the private bullion-owning wealth holders that are leaking gold out to hungry governments and central banks? By definition they are collectively The Powers That Be. Whether they are disaggregated or conspiratorially linked, private gold holders are the true unencumbered savers among us. They are the ones that have a chunk of their wealth in a money form that stores purchasing power no matter what. And unlike fiduciaries overseeing the encumbered wealth of financial asset investors, there is no one and no system between them and their purchasing power.

We suspect most of these quiet savers are quite sophisticated, know exactly what they are doing, and view the preponderance of levered financial assets with suspicion regardless of whatever value they may have relative to one another. (Would it be that much of a stretch to believe these individuals holding trillions in inert rocks might also have great influence over global resources, monetary systems, banking systems and governments?)

Sophisticated Sophism

While Mr. Munger’s comments represent those of a power structure nominally larger and far more organized than private gold holders, it is a power structure that is unsustainable. Financial assets denominated in baseless paper currencies are marked-to-market many times higher than gold presently; however this pricing is only supported by the full faith and credit of a temporary authority, not by sustainable power. Functionally insolvent banking systems are supporting rotating politicians and policy makers, who, in turn, are furiously trying to reverse declining real output stemming from organic pressures for systemic de-leveraging. (During the leveraging process productive capital was greatly misallocated. During the de-leveraging process, it is logical that real productivity is declining.)

It would seem sustainable power no longer resides with the fellows, the institutions or the policies that promote a system in which higher numbers equal the false perception of sustainable wealth. It must reside in the commercial marketplace and among capital holders (those who own sustainable resources or sustainable savings that can buy resources no matter what the inflation-adjusted price is).

The list of well-known baseless money promoters is long. We can start with virtually all central bankers, current, retired or passed-on, throw in virtually all economic and political leaders of the modern era, add icons like Messrs. Munger and Buffett sitting atop a pile of numbers, and, for good measure, leaven the whole meringue with journalists calling upon financiers posing as capitalists for instruction and guidance. It is obvious that the preponderance of people that have ascended to positions of authority has directly benefitted from the financial system and has no incentive to question its merits today.

Is it any wonder Bob Rubin, who gamed the capital markets so well at Goldman Sachs and the FX markets so well at Treasury, chose the academic Larry Summers to follow in his footsteps? Summers, the child of two highly regarded Keynesian economists and the nephew of Paul Samuelson, (the man who literally wrote the book for all budding economists on how to manage economies), leant an air of intellectual rigor to Rubin’s market manipulations. True to form Summers recoiled and shrieked “gold is the creationism of economics!” this past winter in response to a question of whether he thought a gold standard might provide more discipline to runaway fiscal spending. The particular economic canon he and the vast majority of contemporary economists worship is a theory called “political economics“, which assumes sustainable and growing economies are best ensured by actively synthesizing constant demand growth through fiscal, monetary and trade policies, not by overseeing human commercial incentives and the private marketplace. We ask you: which requires more faith?

Nor should we be surprised that Paul O’Neill and John Snow, actual businessmen, were run out of Washington after a couple of years and replaced by a money man, Hank Paulson. The Republican Paulson and the Democrat, New York Fed President, Tim Geithner, (who would replace Paulson after the peaceful transition of power in 2008), bought “illiquid” (i.e. mismarked) bank assets with newly created base money. Demand was temporarily synthesized by bringing future purchasing power forward and effectively transferring it from taxpayers to commercial banks. Though the pain would have been felt only in the financial sector had nothing been done, “independent” policy makers were able to avoid a counter-factual called “deep depression”, and both parties were able to take credit. While politics may stop at the water’s edge, it clearly begins on the corner of Wall and Broad.

Calvin Coolidge said in January 1925 that “the chief business of the American people is business”. He did not say (although 85 years later he certainly might have); “the business of America is having banks create unreserved credit so that the broader economy would then have to focus on repaying its debts to banks.” The difference between the two principles is that the former suggests human industry sorts resources best while the latter institutionalizes producers and consumers into an encumbered mass to be managed by a few. (Again, please forget politics here. We are not advocating how much to tax, who to tax or what to spend it on, only pointing out a corrupt and failing monetary system.)

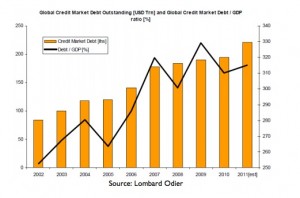

Whether they know it or not, our authority figures today are working on behalf of banking systems. Banks borrow capital from the factors of production and create bookkeeping assets many multiples of that capital for themselves in the form of unreserved credit. Meanwhile, the credit they extend becomes debt for their borrowers, fully-collateralized for banks by the borrowers’ assets and future labor. Fractionally reserved banking systems effectively permit banks to conjure future claims on currency where no currency exists today; creating “when-issued money” from thin air that must eventually be settled by their central banks. This ensures inflation.

Political economics not only accommodates fractional reserve lending — it relies on it. Its aim is to perpetuate nominal demand growth at all times to achieve full employment. This is a noble goal but it has a dark side too. Consistent demand growth requires consistent credit growth, which requires consistent debt growth and, in turn, public servitude to bank lenders. Policy makers ultimately find that inflation becomes an economic imperative in their effort to ease the nominal burden of repaying debts. (The business of America, the next President might say, is finance. This would seem entirely reasonable given that the next president will either be a proven budget buster or a professional leverager – a dismal tie in economic terms, a win in gold terms.)

Piffle & Baffle

Against this backdrop, Munger, Buffett, Bernanke, Geithner, Draghi, Lagarde, Rumpuy, Obama, Romney, McConnell, Boehner, Reid, Pelosi, Kudlow, Krugman, Roubini, Wolf, Hilsenrath, Kernen, etc. etc., seek to instill confidence among the factors of production and investors they influence. They are good and kind, highly intelligent and well-intentioned. But so what? Collectively they are wrong-headed. The fractional reserve banking system and debt money system they help sustain is directly responsible for the wealth and income inequality currently being experienced. (When they yell at the mention of this assertion ask them to disprove it.)

Promoting finance for the sake of financial return when it no longer produces capital cannot work. Arguing about taxes or austerity or budgets or infrastructure spending or political platforms is simply noise as more debt accrues and employment participation rates decline. What exactly is there to be confident about?

And why should perpetuating confidence be the foundation for all centrist economic policies? People at all income levels and of all political persuasions can no longer save their wages in the same currency it is paid. Are we to be confident that the real economy can expand when real wealth declines? Or that investing our excess baseless currency back into shares of productive businesses (denominated in the very same wasting currency) will provide investors with lasting purchasing power? Are we to be confident investing in a system where government, mortgage, corporate and municipal debts are priced at negative real rates because central banks, who will always have more money at their disposal than all bonds outstanding, threaten to continue buying them if need be?

We have met such authority figures and yes, they are usually charming, smart and dynamic. But almost without exception it seems they confuse their theories, (rationalized with econometric models filled with unrepeatable observations), for physical science.

Confidence in productive assets may be more warranted than confidence in bonds and baseless cash, but this does not mean one should have confidence about future real production, wealth creation, economic growth or the post-Bretton Woods monetary system. When the global monetary regime reduces to the solvency of one global banking system with interconnected, uncollateralized receivables, as it does today, then its sustainability relies on: a) the ability and/or willingness of depositors to keep savings in the banking system, (love those debit cards!), and, b) the willingness of the factors of production to continue accepting unreserved currency as compensation and the willingness of capital holders to save and invest in it. As workers, savers, investors, consumers, taxpayers, policy makers and politicians, why should we count on such unwarranted confidence to continue?

It is within this context that Mr. Munger and others urge those curious about gold to start walking upright, to stop dragging their knuckles on the pavement. They counsel civilized people to reinvest their baseless wages into baseless shares of productive businesses selling goods and services in return for baseless revenues and earnings. Do not save in a relatively scarce form of money, they say or imply, (because saving starves creditors and leads to nominal output contraction)! Again, it’s not about nominal anything; it’s about the purchasing power of wages, savings and investment.

Finance may be doomed but commerce is not. Total global bank assets are about $95 trillion and total bank reserves are not quite $10 trillion. This fractionally-reserved global banking system does not necessarily imply immediate economic contraction because there is no obvious catalyst that would force the leverage gap to suddenly close (though the JPM news just hit…). However, substantial bank leverage in combination with already highly-leveraged depositors, capital holders and consumers, are significantly retarding demand and real economic activity. There simply is no natural incentive for lenders or borrowers to leverage their balance sheets further, which in turn means that output growth and asset prices must continue to decline in real terms.

And so we think it would be fair to caution against heeding the advice of a self-interested financial establishment trying to fit a flawed, unsustainable and quickly deteriorating set of theories into what they would like us to believe is a noble and patriotic goal. The common good is not necessarily expressed accurately by past financial asset winners and the ambitious policy makers they support. Their barking is becoming more frequent — a clear sign that their baseless protestations and accusations are failing to turn the tide (not against squeaky pipsqueaks like us, but against fundamental logic, human incentives and the mathematical power of compounding nominal debts).

Don’t Worry, Be Happy

There is no reason to expect the demise of Western hegemony and no need to promote gold. Gold will be priced significantly higher in fiat terms over time, (or next week, who knows), either by the markets or by an administered fiat devaluation. There can be no fiscal solution over any amount of time; growth, austerity or some optimal combination of the two can no longer work. The only way out is massive currency dilution and we expect leaders across the political spectrum in all debtor nations to ensure this occurs.

We have no doubt the same misguided establishment will reverse course to save the day. They will ultimately choose to destroy the burden of repaying domestic debt through monetary inflation, a process that would reward the great majority of voters. They will choose this route because the alternative will be to keep exporting Western capital to developing economies and continued domestic unemployment. (Krugman wins.) By doing so, the West will have successfully shorted its currencies to export economies and will have received cheap imported goods and resources in exchange.

The developed economies of the West will become more vibrant afterwards because the prices of goods, services, labor, assets and liabilities will again reflect market clearing real (de-levered) values. Nominal prices may be unrecognizable but affordability across all income levels will improve. Debtor nations will wipe the slate clean and their factors of production will again be globally competitive.

The key to a successful transition is a credible monetary reset. Gold is the default collateral for money because it has a long and established precedent in this role. All that would be needed would be a fairly equitable distribution of gold among global monetary authorities (taking place now?), and an agreed-upon exchange rate vis-à-vis baseless paper. It would have to be an exchange rate at which central banks could successfully monetize assets by tendering for physical gold with newly manufactured paper money, an exchange rate high enough to attract enough gold to cover unreserved credit held in the banking system. It’s a high figure. The relative cost of holding physical gold today is minimal, (above-ground bullion or in-ground bullion through mining shares), against the negative real returns offered by the preponderance of financial assets in float.

We suggest one keep identities straight; invest with central banks, not against them; and consider the hollow rhetoric of the establishment that may temporarily suppress its paper price “a gift”. They are working for physical gold holders, not against them.

Lee Quaintance & Paul Brodsky